VIEWS ABOUT SULEYMAN DEDE

by Ibrahim Gamard (1/85; revised 1/99, 1/23, 5/24)

|

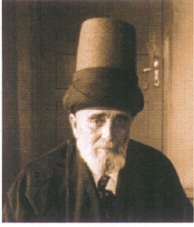

|---|

Suleyman Hayati Loras Dede Efendi has passed into the next world, on January 19, 1985. I have looked at my photographs of him with great fondness. But I have also reflected on the effects of his radical actions to preserve the Mevlevi tradition by spreading it to the West. He appointed quite a few Westerners to the position of Mevlevi sheikh, based on an apparently desperate hope that they would somehow carry on the Mevlevi tradition-- which has been greatly weakened during the past decades. Several of them clearly impressed him as being spiritually advanced. He must have hoped that such individuals would be gradually drawn to Islam, at least to the minimal practices of the religion of Mevlana and the Mevlevi tradition. But of such persons whom I have met who were given the title of Sheikh by him, few have had much attraction toward Islam. It is striking how many such individuals are more committed to Esoteric-Occult, Gurdjieffian, and other (non-religious) mystical teachings rather than to religious mysticism--which is what the Mevlevi tradition is all about.

Mevlana was one of the greatest religious mystics of all time. A devout practicing Muslim, his writings were an inspired elaboration of scriptural verses (from the Qur'ân) and the sayings and doings (ahâdîth) of the Prophet Muhammad. A prominent Rumi scholar [Talat Sait Halman ("The Turk in Mawlânâ/Mawlânâ in Turkey," in Chelkowski's book, "The Scholar and the Saint," New York University Press, 1975) has shown that about six thousand verses of the Mathnawi and Dîvân-i Kabîr are virtual translations into Persian poetry of Quranic verses. A large part of his writings involve very traditional Islamic interpretations of the Qur'ân and ahâdîth. And, of course, a substantial part are devoted to mystical interpretations. Although Mevlana attained a certain universality, his perspective remained Islamic.

The idea that has been promulgated that one can be a Mevlevi and ignore Islamic religious beliefs and practices has been very exaggerated. It is true that in modern times (since the 1950's), Mevlevi shaykhs have accepted people of other faiths to be disciples without requiring or pressuring them to convert to Islam. But they certainly would have hoped and prayed that such persons would eventually become attracted to accept Islam as the foundation of the dervish path.

Mevlevis have been famous for practicing extreme tolerance toward others, yet they have always been strict and disciplined among themselves. Dede Efendi took a radical approach, in an attempt to save the Mevlevi tradition, by appointing more than a dozen non-Muslims in the West to be Mevlevi shaykhs, or spiritual leaders. I believe that this was mostly a mistake, because it resulted in a lack of clear standards of behavior for such leaders, who could easily avoid making any serious changes in their life-styles. Aside from daily practices of Islam, such individuals had no experience of Mevlevi disciplines and practices. It could be argued, however, that Dede had little choice but to try to pass on the tradition to whoever he could who showed a strong attraction to Mevlana and the whirling prayer-- since it was rare for Western students of Sufism to convert to Islam. I was told that traditionally, no Mevlevis were initiated as sheikhs until they had spent many years going through the ranks or stages of the tradition and were then recommended to an official Mevlevi leadership committee. The Makam-Chelebi (a position traditionally held only by a direct descendant of Mevlana, and who lived in Konya for centuries) was the only one who had the power to authorize someone to become a sheikh, including someone who had not gone through the customary preceding ranks.

In view of the mostly disappointing results of Dede's radical approach, perhaps a more conservative approach would be suitable now: There should be standards for someone to become a candidate for the rank of Mevlevi Sheikh, such as: being a practicing Muslim, being the deputy (halife) of a Mevlevi Sheikh, having training in the Sema, being familiar with the works of Hz. Mevlana, and so on. And no Mevlevi leader should be called or considered a Mevlevi sheikh (or sheikha, a woman leader--if that was ever allowed) who is not a practicing Muslim. And perhaps there should be an established procedure for disciplining such shaykhs who fail to live up to Mevlevi standards In regard to this, in 1995, before Jalâluddîn Chelebi died (in April 1996), he was able to clarify that there are Mevlevi standards of expected behavior:

"In order to bring the Mevlevis of the world under one roof, I

recently ordered the establishment of the International Mevlevi

Foundation. One of the most important roles that the Foundation

will assume will be to inform everyone about actions and

applications that are inconsistent with the principles and practices

of Hazret-i Mevlana and also to clarify other issues as and when

this becomes necessary. In this age of freedom, individuals may

choose to behave, think, and exist in any way that is appropriate to

their personality. However, if such inclinations do not conform to

the culture, thinking, and tradition of Hazret-i Mevlana, which

have been clarified in detail over a period of more than seven

hundred years, those people will be considered quite apart and

separate from the principles of Hazret-i Mevlana. In these times

one can observe a spiritual emptiness. Some people, who appear

bright outside and are actually dark inside, take advantage of the

situation. Such people exploit the pure, clear love of Mevlana and

compromise its integrity. I pray to God that our foundation will be

one that organizes the teachings and principles of Mevlana and one

that gathers people around his love. May the light of Islam and the

love of Mevlana be upon you."

--Dr. Jalâluddîn Muhammad Bâqir Chelebi.

(See also the Chelebi family website.)

Hopefully, Dr. Chelebi's son and successor, Fârûk Hemdem Chelebi, will further his father's aspirations in order to protect and guide this precious tradition.

I am convinced that Suleyman Dede (may God pour blessings upon his soul), if alive today, would be very pleased to see the establishment of such improved standards for Mevlevis. This should help the Mevlevi tradition-- the tradition of Hazrat-é Mevlânâ Jalâluddîn Rûmî (may God be well pleased with him)-- not only to survive, inshâ 'llâh--God willing), but to flourish on a more solid foundation, while welcoming all to enter the rose garden of Divine Love.

TOWARD A BIOGRAPHY OF SULEYMAN HAYATI LORAS DEDE

The following are views of Suleyman Dede that I have collected for many years. These are often conflicting and hard to reconcile. The differences between Westerners who studied with him in Turkey and Turks who knew him personally for many years are striking: Western disciples view him as a wise, and sometimes cunning, Sufi master who radiated spiritual love and grace. However, Turks who knew him for many years viewed him primarily as a "cook." This was, perhaps, because their contact with him was mainly during the months of Ramadan, when he came to Istanbul to cook for the Chelebi family. The Turks that I contacted who knew him for decades called him "Suleyman Dede" but regarded "Dede" as a nickname; none believed (but one, a former disciple) that he had lived in the Mevlevi lodge (tekke) in Konya prior to 1925. In contrast, Westerners tend to view him as someone who had lived in the tekke; some also believe that he was a student of Sidke Dede (the most prominent of Mevlevis, after the Makam Chelebi, who lived in the Konya tekke). If, indeed, he had lived in the tekke, he could not have completed the 1,000 day retreat because, according to Friedlander, "Osman Dede is the only living person to successfully go through the three year Mevlevi chille (retreat). He is known by the Mevlevis as "Chille Dede" (The Whirling Dervishes, p. 101, 1975).

A biography is hardly possible, as there are few facts about his life that can be corroborated.He was born in Konya but there are different views about the date. The engraving on his tombstone is 1904. However, according to a long-time disciple (since 1972): "Dede was born before 1908, probably 1892-94." And: "From other times I recall conversations in which it was generally acknowledged that he was born ca. 1898. It was seven years later when he died, aged ca. 84" (David/Da'ud Bellak, personal email, 11/10). Another long-time disciple (since 1973) stated that Dede did not know when he was born (Wolf/Suleyman Bahn, personal email).

There are different views about when he first started to visit the Mevlevi lodge [tekke] in Konya. According to Da'ud Bellak: "He entered the Tekke (by his own account) when he was 12." And: "On another matter, it was in a story about himself that he mentioned going to the Tekke at age 12. Whether this was in residence, or taking the commitment, I don't know, but I'm left with the fairly clear impression formed at the time in Turkish that it was in residence." According to a published interview, Dede is quoted as saying (if translated correctly): "When I was 18 I entered the monastery and worked in the kitchen. I worked in the kitchen for twenty-three years" (The Movement Newspaper, June 1976). When I asked Guzide Chelebi (the widow of the late Makam-Chelebi, Jelaleddin Bakir Chelebi) if Suleyman Dede had contact with the Konya tekke before 1925 (when it was closed and later made into a museum), she said: "No. He was too young" (personal interview, 12/18.) However, Abdulbaki Baykara (a Mevlevi Sheikh) told me that he was told by his father (also a Sheikh and son of the last Mevlevi Sheikh of Yenikapi Mevlevi Lodge) that Suleyman Loras did work in the kitchen inside the tekke, but as an outside day worker, an assistant cook. He added that it was quite common for Mevlevi tekkes to hire day laborers when they were short on help (private telephone call, 3/21).

There are differences about how he came to be called "Dede" ("Grandfather" in Turkish; formerly a title given to someone who had completed the arduous 1001-day retreat ["chille"], which was centered on work in the kitchen). According to Da'ud Bellak: "He was made a dede at ca. age 18." But according to the 1976 interview, Suleyman Dede said: "After being there for twenty-three years, they gave me the title of Dede and I received a cell, and I didn't work in the kitchen any more." According to long-time Mevlevi, Nezih Uzel, Suleyman Loras was affectionately called "Ashchi Dede" (the title of the chief cook, but usually the trainer of dervishes in a Mevlevi tekke) by Izzet Chelebi, the widow of the late Makam-Chelebi, Mehmet Bakir Chelebi (rumored account). Guzide Chelebi also told me: "He worked as a cook to feed the Mevlana Museum guards. One day he said, 'I have been working in the kitchen for thirty-five years, which is more than equivalent to the 1,001-day chille--so I should be called "Dede."'And this was accepted." According to Dr. Erdogan Erol (a former Director, and a historian, of the Mevlana Museum), Suleyman Loras cooked rice that was so delicious that he was called "Ashchi Dede" (personal interview, translated by Makam-Chelebi, Faruk Hemdem Chelebi, 12/22).

There are different views about whether Suleyman Dede was or was not the disciple of Sitki Dede (the last Mesnevi reciter and teacher, as well as a preacher in the nearby Selimiyye Mosque). According to Da'ud Bellak, Suleyman Dede told him that he was the student of Sitki Dede, and that after the latter's death (in 1933), he used to visit his grave. According to a former disciple of Suleyman Dede, who contacted me by email: "He got his Dede title from 1001 days of education." And: "Süleyman Hayati Dede was the first dervish to Filibeli Hüseyin Sitki Dede" (Mete Üge, 11/17). However, Dr. Erol told me that after the Konya tekke was closed in 1925, "Sidki Dede left Konya." (Sitki Dede's body was subsequently brought to Konya and buried in the Uchler Cemetery.) When I asked directly: "Then Suleyman Loras was not the student of Sitki Dede?" he said, "No." He also said, "He did not do the chille" and that he never worked inside the tekke before its closure.

There are differences about when Suleyman Dede was authorized as a Mevlevi sheikh. Da'ud Bellak has insisted that he was authorized by Makam-Chelebi Mehmet Bakir Chelebi (d. 1944), However, Makam-Chelebi, Faruk Chelebi, has said that this was not the case. The following was told to the author of this article by Guzide Chelebi, the 91 year-old widow of Jelaleddin Chelebi, the previous leader of the Mevlevis (d. 1995) during an interview in December 2018, translated by Makam-Chelebi Faruk Hemdem Chelebi: Suleyman Loras worked as a cook. For many years, he used to travel to Istanbul during (the fasting month of) Ramadan to cook for the Chelebi famly (and their many guests). One year when he came, he told Jelaleddin Chelebi that he was pressured (by Mevlevis in Konya) to lead the Sema (the Whirling Prayer Ceremony), but that he told them he would not do so without the Makam-Chelebi's permission. So he authorized him to be a Mevlevi shaykh. Asked what year this was, she said it was two years after a military coup. (This occured in 1960, so the year was 1962, as confirmed by this date on the photograph below (click to enlarge) that shows Suleyman Dede (right), Enver Turunch Chelebi of Afyon, center), and Selman Tüzün (left, the Mevlevi shaykh in Friedlander's 1975 book, "The Whirling Dervishes"). And Da'ud Bellak recalled that Dede said that he was authorized as a sheikh at the same time as two other Mevlevis-- evidently what the photo below shows.

|

|---|

And there are different views about how much authority Suleyman Dede had as a Mevlevi leader. According to a long-time disciple (since 1977), Dede told her that his appointment as sheikh by Makam-Chelebi, Jelaleddin Chelebi, was as the latter's vekil (or vice-regent with similar authority for a period of time). This was because J. Chelebi could not live in Konya (due to the anti-Sufi law) and welcome visitors to Rumi's mausoleum. She agreed with the view that Dede was the "acting leader of the Mevlevis" at the time. Asked if Dede had the authority to initiate people as new shaykhs, she said that he did not, but that he believed that doing so was from the guidance of Hz. Mevlana (Barihuda Tanrikorur, private conversation, 1977; in an email years later). The fact that Dede was the Makam Chelebi's sheikh in Konya seems to have developed into a divergent view: that Dede, as the "Shaykh of Konya," was deputized with equivalent authority (including as the acting leader of the Mevlevis who had the power to authorize new sheikhs). It was probably Reshad Feild who first called Dede the "Sheikh of Konya." However Da'ud Bellak wrote that, "The reference, 'Sheikh of Konya' was not one that Dede ever referred to in any conversation." And, according to Makam-Chelebi, Faruk Chelebi Efendi, there was no such title and Dede had no more authority than other Mevlevi sheikhs in Istanbul and elsewhere at the time.

According to Suleyman Bahn Efendi, the Mevlevi Sheikh in Germany, Dede's authority and good reputation in Turkey deteriorated as a consequence of his authorizing Reshad Feild, a non-Muslim, as a Mevlevi sheikh in 1976. He wrote:

"At Sheb-i Arus in 1977, the first scandals happened in Turkey. Reshad Feild came with some pupils to Konya. Two American girls from this group danced in public on the road in Sema costumes. This was a real annoyance for the Turkish people. Also it came to common knowledge that Dede had declared Reshad a sheikh, etc. The Turkish television brought reports and the newspapers wrote about it. Dede was now the target of violent attacks. There was large controversy under the regular sheikhs. The Mevlevi movement in Turkey split from now on into two groups. One pro Sueleyman Dede and one against him. From now on he also did not stand any more on the post in Konya [during Sheb-i Arus]. He concentrated his strength from now on to his tasks in the USA. In Turkey, the Makam Dede - at that time, Jelaluddin Chelebi - was still on his side. But the fact that he had simply made a man who is not Muslim to a Khalifa was too much. Dede asked for some time, so that he could work with Reshad. He also became more and more ill. The whole affair probably had pressed him harder than he would have admitted. He really thought that he could convince Reshad to become Muslim. Reshad, however, did not want to. He was not at all interested to go deeper into the Mevlevi tradition, but he wanted to use the tradition for his own aims. He wanted to use Dede to place himself in the limelight. Of course this was recognized by Dede and he reacted accordingly later.... In the meantime in Turkey, many persons did not accept Dede as a sheikh any more. He had laid down also all relevant offices. Also in Germany until some years ago it was said that he had never been a genuine sheikh. I know cases of Turks who came to him as searching people, to whom he said: 'I am not a sheikh, search elsewhere, I cannot help you.' At the same time he also had visions that he would die soon. This also applied, However, on another level. In this time he often said 'Goodbye' to me." (Bahn, email, 5/03)

Unfortunately, major differences within the Mevlevi movement have continued up to the present time. These mostly concern the Makam-Chelebi, the central authority in the Mevlevi tradition--and in particular, the issue of the authority to appoint new Mevlevi sheikhs. Some Mevlevis do not understand or accept that the Mevlevi Order is different from most other Sufi orders in that only the Makam-Chelebi is allowed to authorize new sheikhs--not the sheikhs themselves. Suleyman Dede violated this tradition by authorizing new sheikhs without the consent of the Makam-Chelebi. As a result, most Westerners who identify themselves as Mevlevis--especially those whose lineage derives from Suleyman Dede--have ignored the Makam-Chelebi and know little about him and this important Mevlevi tradition. A further consequence of this is that the Mevlevi tradition as a whole, already weakened by the 1925 anti-Sufi law, is further weakened by such divisions.

See also "Memories of Suleyman Dede Efendi"